sh:/tmp# mount | awk '/^\/dev/ { print $1,$4,$5 }' | sort -u

/dev/mapper/vg-lvb type ext3

/dev/mapper/vg-lvc type ext3

/dev/mapper/vg-lvd type ext3

/dev/mapper/vg-lv--root type ext2

/dev/mapper/vg-lv--tmp type ext2

/dev/mapper/vg-lv--usr type ext4

/dev/mapper/vg-lv--var--log type ext4

/dev/mapper/vg-lv--var type ext4

/dev/sda1 type xfs

Yes, I know

About the Execute Bit

I follow @UnixToolTip by John D. Cook on Twitter.

In a recent tweet, he mentioned chmod +x as a way to make a file executable on Unix/Linux, and some people complained that was so obvious it did not deserve to be qualified as a "tip."

As of myself, I find any piece of information valuable. Especially for new users. Moreover, that gave me the idea of writing a short column about that x permission bit. After all, it may appear cabalistic when initially encountered, and there are some amusing corner cases that worth being described.

The permission bits

To start, let’s go back to the very basics. It is the role of the filesystem to organize things on a disk so you can store and retrieve your files. There are numerous different filesystems supported on a typical Linux system: Ext3/4, XFS, ZFS, BTRFS just to name a few. A filesystem has the exclusive use of a given storage area. However, if you have multiple disks or multiple partitions on the same disks, you may very well have different kinds of filesystems in use simultaneously on your system.

For example here are the filesystems currently in use on my laptop while I type this text:

The job of the file system is to store and retrieve your files. In addition to the file content, they also manage a set of metadata associated with that content. It could be, for example, the file name, the file owner, the latest modification date, or, for what interest us today, the file’s permissions.

For things to be a little bit less abstract, let’s consider that sample file:

sh:/tmp# touch samplefile sh:/tmp# stat samplefile File: samplefile Size: 0 Blocks: 0 IO Block: 4096 regular empty file Device: fe09h/65033d Inode: 274 Links: 1 Access: (0754/-rwxr-xr--) Uid: ( 1000/ sylvain) Gid: ( 50/ staff) Access: 2018-03-13 19:12:41.572964286 +0100 Modify: 2018-03-13 19:12:41.572964286 +0100 Change: 2018-03-13 19:14:58.119559243 +0100 Birth: -

You can see many metadata are associated with the file. You may eventually be more familiar with the output of the ls -l command that displays the most useful subset of that information:

sh:/tmp# ls -l samplefile -rwxr-xr-- 1 sylvain staff 0 Mar 13 19:12 samplefile

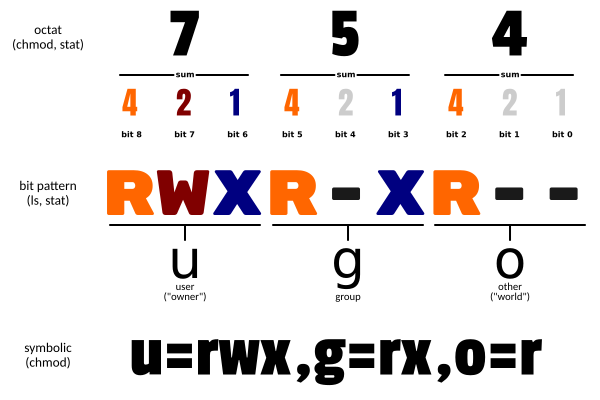

The traditional file permissions (as opposed to Unix ACLs) are stored using at least 9 bits. A bit is just a fancy name for a flag that can be either true ("set") or false ("clear"):

-

The bits 0 to 2 respectively control the write, read and execute permissions on the file for any user (for the "world")

-

The bits 3 to 5 respectively control the write, read and execute permissions on the file for users belonging to the same group as the file

-

The bits 6 to 8 respectively control the write, read and execute permissions on the file for the owner of the file.

For my sample file, you can see:

-

anyone on the system can read that file (

r--) -

the members of the staff group can read and execute (

r-x) that file -

and finally sylvain, the owner of the file, can read, write and execute that file (

rwx) If you study thestat(1)/ls(1)commands output, you may see there are room for other "permission" bits. However, we will not talk about them today.

Instead of the symbolic rwx flags, you will sometimes encounter their numeric octal counterpart. In that format, the x flag has the value 1, the w flag has the value 2, and the r flag has the value 4. So, rwx can be written numerically as 7 (that is: 4+2+1). I let you make the necessary calculations to check that, as indicated by the stat command, the rwxr-xr-- permission is equivalent to the octal number 754:

stat -c "%a %A %n" samplefile 754 -rwxr-xr-- samplefile

changing permission bits

When talking about standard Unix permissions, we cannot avoid mentioning the chmod(1) command. It is the canonical tool to change file permissions. Here also the permission can be specified either as numerical values or as symbolic values. In that latter case, the syntax is somewhat different from the output of the ls and stat commands. Here are a couple of examples:

Set absolute permissions |

|---|

sh:/tmp# chmod 622 samplefile sh:/tmp# chmod u=rw,g=w,o=w samplefile sh:/tmp# stat -c "%a %A %n" samplefile 622 -rw--w--w- samplefile |

Add new permissions |

sh:/tmp# chmod +1 samplefile sh:/tmp# chmod o+x samplefile sh:/tmp# stat -c "%a %A %n" samplefile 623 -rw--w--wx samplefile |

Remove permissions |

sh:/tmp# chmod -433 samplefile sh:/tmp# chmod u-r,g-wx,o-wx samplefile sh:/tmp# stat -c "%a %A %n" samplefile 200 --w------- samplefile |

As an exercise to check your comprehension, I let you now complete the following table:

| numerical permissions | symbolic permissions | effect |

|---|---|---|

chmod 600 … |

set |

|

chmod ugo=r … |

set only read permission for everyone |

|

chmod u+w … |

add the write permission for the owner |

|

chmod -337 … |

Alternate usage of the x bits

Unix-like systems do not have the notion of "executing" a directory. So the x bits, when applied to directories, has a different meaning. It is used to grant the right to traverse that directory.

The difference between the x and r bits for directories are easier to grasp on an example. So, let’s create first a directory containing a couple of dummy file:

sh:/tmp# mkdir d sh:/tmp# echo echo hello > d/f1 sh:/tmp# echo echo world > d/f2 sh:/tmp# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 13 23:44 d -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f1 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f2

Let’s remove now the x permission on the directory:

sh:/tmp# chmod -x d sh:/tmp# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 drw-r--r-- 2 root root 4096 Mar 13 23:44 d -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f1 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f2

Now let’s see what the unprivileged user with id 1000 can do with that directory:

sh:/tmp# sudo -u '#1000' ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 ls: cannot access 'd/f1': Permission denied ls: cannot access 'd/f2': Permission denied drw-r--r-- 2 root root 4096 Mar 13 23:44 d

As you can see, despite the r permission, the ls command is not allowed to access the files stored in the directory. For things to be clear, you have to understand with those permissions, the user with id 1000 can read the list of files contained in the directory. However, (s)he cannot access anything through that directory (including the file’s metadata):

sh:/tmp# sudo -u '#1000' ls -l d ls: cannot access 'd/f1': Permission denied ls: cannot access 'd/f2': Permission denied total 0 -????????? ? ? ? ? ? f1 -????????? ? ? ? ? ? f2

sh:/tmp# sudo -u '#1000' cat d/f1 cat: d/f1: Permission denied

Let’s permute now the r and x flags so that users may have the traversal right, but no longer the read permission on the directory:

sh:/tmp# chmod +x-r d sh:/tmp# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 d-wx--x--x 2 root root 4096 Mar 13 23:44 d -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f1 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f2

And do out little experiment again:

sh:/tmp# sudo -u '#1000' ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 d-wx--x--x 2 root root 4096 Mar 13 23:44 d -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f1 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f2

sh:/tmp# sudo -u '#1000' cat d/f1 echo hello

Interesting. Despite the missing r permission on the directory, the user was able to access the files stored in there. But only because I explicitly gave the path to those files on the command line. This implies I knew these file name in advance. However, with that setup, the user is no longer able to access the directory content—so (s)he cannot obtain the list of files contained in the directory:

sh:/tmp# sudo -u '#1000' ls -l d ls: cannot open directory 'd': Permission denied

This feature that can be used to implement a basic kind of access control: by using a traversable but unreadable directory, you can grant people the right to read the content of files they know to be in that directory. However since the same people cannot see the list of files contained there—they cannot know if there are other files in that directory, and without their name, they cannot read them.

What if the filesystem does not support the x bit.

I have said it earlier, modern operating systems support many different kinds of filesystems, including filesystems unable to store the Unix permission bits.

Let’s create a 512MiB VFAT disk image for the purpose of testing:

sh:/tmp# dd if=/dev/zero of=vfat.img bs=1M seek=511 count=1 sh:/tmp# mkfs -t vfat ./vfat.img sh:/tmp# mount ./vfat.img /mnt sh:/tmp# pushd /mnt

And let’s now populate our newly created file system with the same files as above:

sh:/mnt# mkdir d sh:/mnt# echo echo hello > d/f1 sh:/mnt# echo echo world > d/f2 sh:/mnt# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 14 00:13 d -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 6 Mar 14 00:12 d/f1 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 6 Mar 14 00:13 d/f2

You may have notice the FAT 32 filesystem add the implicit x permission on every created file or directory. And you can’t change it using chmod because that filesystem does not handle the standard Unix permissions at all:

sh:/mnt# chmod -R -x d sh:/mnt# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 14 00:13 d -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 6 Mar 14 00:12 d/f1 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 6 Mar 14 00:13 d/f2 sh:/mnt# chmod -R -xrw d sh:/mnt# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 14 00:13 d -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 6 Mar 14 00:12 d/f1 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 6 Mar 14 00:13 d/f2

Since that particular filesystem does not handle Unix permissions, some default value is provided by the operating system to userspace applications. Those default values are controlled filesystem-wise by specifying the fmask option at mount time. The fmask option is a mask, that is the list of permission that should be removed. For example, to remove the x flag to all files of my VFAT filesystem, I can mount it like that:

sh:/tmp# popd sh:/tmp# umount /mnt sh:/tmp# mount ./vfat.img /mnt -o fmask=111 sh:/tmp# pushd /mnt sh:/tmp# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 d-wx--x--x 2 root root 4096 Mar 13 23:44 d -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f1 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 13 23:44 d/f2

In addition to the fmask option, the mount command when applied to VFAT filesystems accepts the dmask option whose purpose is similar, but to apply a permission mask to directories rather than files. I let you experiment with the dmask option as an exercise.

noexec

Finally, if you want to prevent execution from a given filesystem you can also use the noexec mount option:

sh:/tmp# mount ./vfat.img /mnt -o noexec sh:/tmp# pushd /mnt /mnt /tmp sh:/mnt# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 14 00:13 d -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 11 Mar 14 00:12 d/f1 -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 11 Mar 14 00:13 d/f2 sh:/mnt# ./d/f1 bash: ./d/f1: Permission denied

As you can see despite the x bit, we do not have the permission to run any executable file from that mount point. The noexec option is particularly useful if you want to prevent execution from a filesystem that otherwise supports standard Unix permissions. That way, you can still manipulate the permissions as usual, but no binary executable can be run. Particularly useful for removable media or kiosk systems.

To see the noexec flag in action, let’s create and mount an ext3 filesystem this time. This is a Linux filesystem that has full support for the standard Unix permissions. In that initial step, we will mount it without any specific option to observe its default behavior:

sh:/mnt# popd sh:/tmp# dd if=/dev/zero of=ext.img bs=1M seek=511 count=1 sh:/tmp# mkfs -t ext3 ext.img sh:/tmp# mount ./ext.img /mnt sh:/tmp# pushd /mnt /mnt /tmp sh:/mnt# mkdir d sh:/mnt# echo echo hello > d/f1 sh:/mnt# echo echo world > d/f2 sh:/mnt# chmod +x d/f1 sh:/mnt# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 14 00:31 d -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 11 Mar 14 00:31 d/f1 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 14 00:31 d/f2 sh:/mnt# ./d/f1 hello sh:/mnt# ./d/f2 bash: ./d/f2: Permission denied

As you can see, the x flag is user-settable, and, as expected, when present for a file it will grant the execution right on that file. And now, let’s remount the same filesystem, but this time with the noexec options:

sh:/mnt# popd /tmp sh:/tmp# umount /mnt sh:/tmp# mount ./ext.img /mnt -o noexec sh:/tmp# pushd /mnt /mnt /tmp sh:/mnt# ls -ld d d/f1 d/f2 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 14 00:31 d -rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 11 Mar 14 00:31 d/f1 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 11 Mar 14 00:31 d/f2 sh:/mnt# ./d/f1 bash: ./d/f1: Permission denied sh:/mnt# ./d/f2 bash: ./d/f2: Permission denied

Permissions on the filesystem haven’t changed. Nevertheless, the kernel prevents the execution of any file from that filesystem now, regardless the presence or absence of the x flag on that file.

For a little bit of magic

To conclude that article with a little bit of magic, using a combination of bind mount and remount on a Linux system, you can mount the same filesystem on two different mount points, one with exec permissions, the other one without it:

sh:/mnt# popd /tmp sh:/tmp# umount /mnt sh:/tmp# mkdir /root/backdoor sh:/tmp# mount ./ext.img /root/backdoor -o noexec sh:/tmp# mount --bind /root/backdoor /mnt sh:/tmp# mount -o remount,exec /root/backdoor sh:/tmp# /root/backdoor/d/f1 hello sh:/tmp# /mnt/d/f1 bash: /mnt/d/f1: Permission denied

Since the options are enforced when the filesystem-level is mounted, the "trick" here is to use two real mounts (the initial one, and the remount one) with two different sets of options. Because of the "remount" option, this is actually different from mounting twice the same filesystem--something that isn’t supported by most of them (with the notable exception of shared disk filesystems like OCFS2). But we are entering now the realm of very specialized tasks. If I follow that path, I risk being more confusing than helpful, especially if you are new Unix-like systems. So, instead, take your time now to examine and experiment with the different example shown in that article to try figuring how they work. It is definitely the best way to understand your system!